Planning for Learning, Not Just Strategy

Recently, I read a post by Carl Hendrick called Bright Lines: How to Use Interleaving. It’s a great read. He explains how interleaving makes learning feel harder in the moment, but actually helps students remember more in the long run. That idea really stuck with me.

Carl explains that interleaving isn’t just switching things up for the sake of it. It works best when you mix similar types of problems or ideas. It makes students stop and think about what strategy they need to use. That moment of having to choose is where the learning happens. In one of his previous posts, A Short Guide to Interleaving, he goes further. He says interleaving only really works when students already have the knowledge to tell ideas apart. If they don’t, it just creates confusion.

Reading both posts made me reflect on how we’ve been changing our own teaching in my context. We’re not claiming to have it all sorted. We haven’t nailed spacing or interleaving across the board. But we’ve started to design our curriculum and routines so teachers can make this kind of learning possible. We’re thinking more about what needs to be revisited, when, and how.

A year ago, I would have said, “We already revisit things. We do reviews at the end of the unit.” I didn’t fully understand how important it is to space content throughout the term, or to mix in older content on purpose. Carl’s post helped me see the difference between revisiting something and designing for remembering.

Here’s what it looks like so far:

In phonics and spelling, we deliberately bring back sounds and patterns that were taught weeks earlier. They show up again in dictation, editing, and reading tasks. Not just as revision, but as part of the work.

In grammar, we keep circling back to the basics. If we’re teaching complex sentences, we’re also revisiting things like verbs, conjunctions, and punctuation. Students aren’t just building new knowledge, they’re reinforcing what’s already there.

In maths, we’re mixing up problem types more often. Instead of just doing ten subtraction problems in a row, we’ll throw in addition, patterns, and place value. That way, students have to think about which strategy to use instead of just following the same steps. We’re also making sure big ideas like regrouping and partitioning keep coming back across the term, not just in one unit.

In our daily reviews & Do Nows, we include questions from last week, last month, and even last term. The aim isn’t just to see what students remember. It’s to strengthen memory by bringing things back just as they’re starting to fade.

It’s not always smooth. Sometimes it feels messy. But students are remembering more. They’re more confident when earlier content reappears. And we’re seeing fewer of those “we just did this last week, how did you forget?” moments (you know, those moments we always have as teachers).

Bjork calls this kind of effort a “desirable difficulty.” When learning feels a bit harder, it actually strengthens memory. Interleaving taps into that because it gets students retrieving, spacing out their thinking, and doing a bit of productive struggle. It doesn’t always feel neat, but it works.

Carl also makes the point that really matters here. He says we need to stop treating the science of learning like a checklist. Retrieve. Interleave. Space. Repeat. It’s not about ticking boxes. These aren’t just strategies to try, they’re principles that depend on what we’re teaching, who we’re teaching, and where students are at.

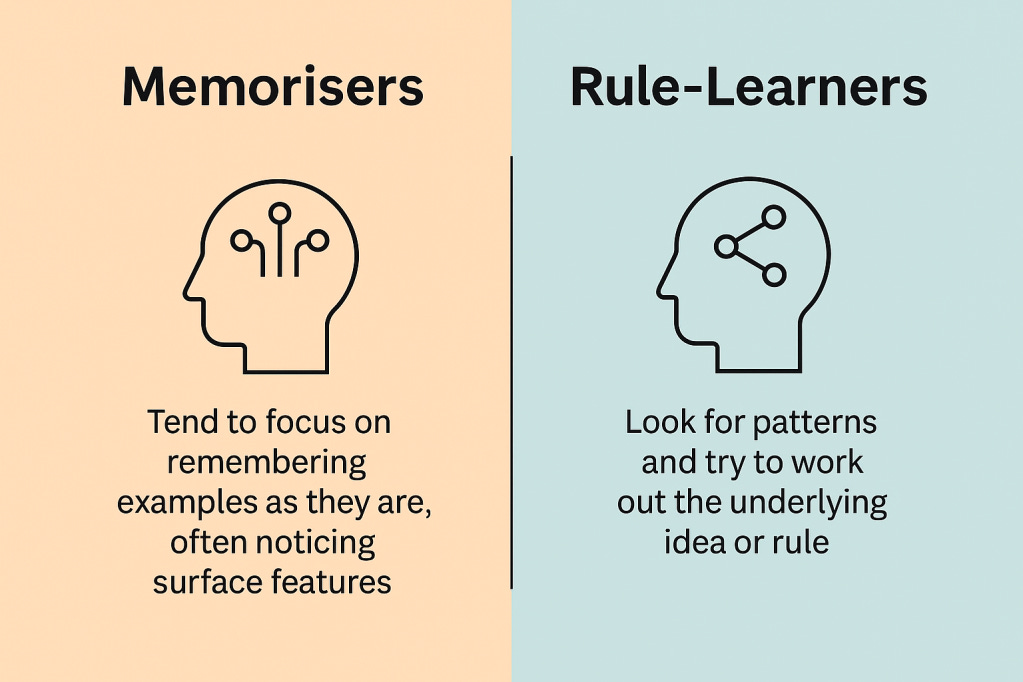

One of the most interesting things Carl highlights is how students approach learning in different ways. Some students are what you might call memorisers. They tend to focus on remembering examples as they are, often noticing surface features. Others are rule-learners. They look for patterns and try to work out the underlying idea or rule that ties things together. How students approach a task can change what kind of practice actually helps them most.

Carl mentions a study where memorisers improved more when examples were interleaved because they needed to see the differences between them. Rule-learners did better with blocked examples because they needed time to notice consistent patterns within a single category. This was new learning for me. I’d always thought interleaving was just some we should do, but I hadn’t considered how the way a student is thinking, whether they’re trying to memorise or abstract a rule, could change what kind of practice helps most.

This is backed up by a 2019 meta-analysis by Brunmair and Richter. They reviewed dozens of interleaving studies and found that it tends to work best for learning that involves distinguishing between similar concepts; not just any kind of material. They also pointed out that interleaving is less effective when students haven't go the required background knowledge needed to make those distinctions. Interleaving needs to match the task and the learner.

This really shifted how I think about task design. What kind of thinking do I want students to practise here? If they’re new to a concept, they might need blocked examples to see the pattern. If they’re further along, interleaving might give them the challenge they need. That’s something I’ll be thinking more about. Not just what to include, but how students will actually think through it.

I’m still figuring out how to do this well across different ability levels. How do we give enough challenge without confusing students entirely? What does interleaving look like when students have patchy prior knowledge? These are things I’m still working on.

Interleaving needs to match the task and the learner.

That’s the real takeaway. It’s not just about using a strategy. It’s about knowing when it helps, why it works, and who it’s right for. That’s the kind of thinking we’re trying to bring into our planning and practice.

So thanks Carl. Your posts helped me reflect on the work we’re doing and why it matters. The next step for us is getting better at asking not just what should I teach? but how will students think about it, forget it, retrieve it, and use it again? That’s the kind of planning that leads to learning that lasts.